Fun with Gravitational Physics and Python

While reading about how my favorite programing language (Python) was used to develop the first ever image of a black hole, I felt inspired to use the language to do some gravitational physics of my own. Mind you, I am not a physicist, nor do I have an extensive mathematical background, so I certainly was not using Python to do anything that was terribly complicated. Instead, I was using it to do more simple, but still productive (not to mention fun) calculations. So, without further ado, let’s get to it.

In this post, we will be exploring using Python to do calculations pertaining to both Newtonian gravitational physics, and even a little general relativity.

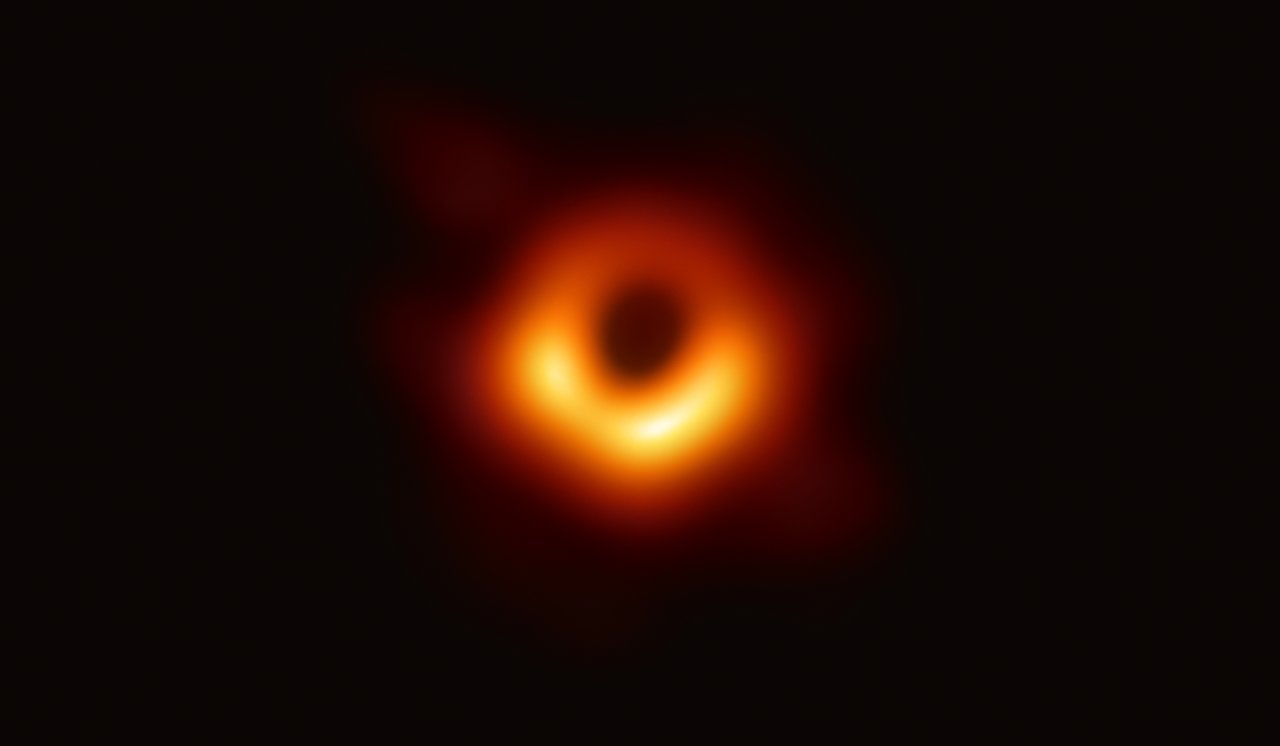

Python was a big part of this. Photo credit: ESO.

Python was a big part of this. Photo credit: ESO.

Calculating Gravitational Attraction

First, we will be creating a Pythonic implementation of the equation that Sir Isaac Newton developed to describe the gravitational forces (in Newtons) between two massive bodies. The equation is: F = Gm1m2/r^2, where G is Newton’s gravitational constant, m1 is the mass of the first body, m2 is the mass of the second body, and r is the distance (in meters) between them.

# Calculate the gravitational force between 2 objects

def grav_force(m1, m2, r):

# Newtons constant

G = 6.674*(10**-11)

formula = G * (m1 * m2 / r)

return round(formula, 2)

To test this function, I tried to calculate the gravitational force between the Earth and the Moon, which when calling the function looks like: grav_force(5.98*(10**24), 7.34*(10**22), 385000000)

Where our first parameter is Earth’s mass, the second is the Moon’s mass, and the third is the distance between them, in meters. The result it calculated was about 1.98x10^20 Newtons, rounded.

Escape Velocity

Another calculation we can easily do with a Python function is escape velocity, or the velocity needed to escape a massive object’s gravity. This is calculated by taken the square root of two times Newton’s constant, times the mass of the body being escaped, divided by the distance from the center of mass. In Python, we would write this something like the following:

def escape_velocity(m, r):

# Newtons constant

G = 6.674*(10**-11)

formula = sqrt(2*G*m/r)

return round(formula, 2)

Using Earth as a test case, we would pass in 5.98*(10**24) for Earth’s mass, and 6378000 (meters) for its radius when calling the function. This will return 11187.07, or about 11 kilometers per second, which is the correct escape velocity for Earth. However, enough classical mechanics. Let’s move on to some general realtivity.

Finding the Schwarzchild Radius

No, I am not going to be doing exact solutions to the Einstein Field Equations, or anything that is well beyond the scope of my personal math and physics knowledge. Instead, we are going to write a function to calculate an object’s Schwarzchild radius. A Schwarzchild radius is a prediction made by German physicist Karl Schwarzchild (hence the name), who found the first exact solution to Einstein’s field equations, and in the process, mathematically predicted the existance of black holes. In the context of black holes, the Schwarzchild radius can be described as the distance between the event horizon and the singularity at the center. Remember, that due to the extremely warped spacetime geometry of a black hole, we cannot not simply use the rules of conventional Euclidean geometry to find its radius, so instead we calculate its Schwarzchild radius by multiplying two times Newton’s constant, times the mass of the black hole, and divide that by the square of the speed of light, or rs=2GM/c^2. Written as a Python function, this would look something like the following:

def get_schwarzschild_radius(mass):

# Convert solar mass to kgs

kgs = mass * (1.989*10**30)

# The speed of light in a vacuum

c = 299792458

# Newton's constant

G = 6.674*10**-11

# Define the Schwarzschild radius

rs = 2 * G * kgs / c**2

return round(rs, 2)

Where the mass parameter is the mass of the black hole in solar masses, not kilograms. I used Cygnus X-1 (weighing in at about 14.8 solar masses), the first discovered and closest known black hole to Earth, as a test case for the function. This yielded a Schwarzchild radius of about 43.7 km, which seems to be accurate, according to sources. I should also note that Karl Schwarzchild developed his solution on the battlefields of World War I, in between calculating artillery bombardments. Yeah, that’s pretty metal.

Summary

While the math we are doing here is ultimately pretty simple, as far as physics goes,it nonetheless shows how one can easily do at least centain physics equations with only a little bit of code. Hope you enjoyed it, and don’t use it to cheat on your physics homework haha.